Since the resurgence in popularity of pagan spirituality began, there has been a dramatic increase in interest pertaining to the mystical practices of cultures whose histories and traditions have largely been buried by time and dominance by foreign religions. One of the major aspects of Germanic spirituality and magical practice that has become popular over time is that of the runes. Around the year 1250 AD, Ólafur Þórðarsson hvítskáld published the first written account of runic knowledge in what is now known as his Third Grammatical Treatise. This work primarily described the techniques of writing with runes, comparing them with the Latin alphabet, but it also mentioned the names of several of them, giving supporting evidence for those names being used at that point.

In 1599, Johannes Bureus of Sweden published the first piece of esoteric runic knowledge to be seen since the decline of the original heathen practices. His work revealed a nineteen-character futhark set, also known as the Dalecarian Runes [1]. The characters of the set are: fä/fyr/frygh, ur, þors, oðas,reðr, kön/kaghn, haghal, noð/nöð/noðr, is/iðr/ir, ar/ars, sol, tiðr/tyr, birkal/biörk, laghr, maðr,stupämaþr, ar-laghr, tveslungan-maðr and bälgh-þors. The Delecarian runes were not an ancient set, but rather were from a region in Sweden where runes were still being used for writing purposes. Bureus, however, had some character flaws which contributed to his views on the esoteric nature of the runes. He believed that the Jews had stolen their writing system from the original runic system, and had used it to write the Kabbalah. This meant to him that the runes, which were stolen from God’s chosen people, the Swedes, were the original “Gothic” Kabbalah. Therefore, he applied Kabbalah lore and techniques to the runes in his attempt to restore the “true” knowledge of the elder runes.[2]

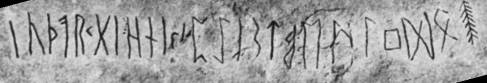

Arngrímur Jónsson later published more runic information which was still known in Iceland, revealing a twenty-one-character set in alphabetical order. The primary difference between this set and Bureus’ set was the introduction of the “Stunginn” or “dotted” runes, which were used to denote phonetic differences [3]. For example, whereas Kaun generally represents a [k] sound, Stunginn Kaunrepresents a [g] sound. These and a couple of other examples are shown in the following image of Swedish runes, c. 1000 AD:

http://media.tumblr.com/0ff7cada4d4beacf3a6ba3ad24322f1d/tumblr_inline_msc459JjFA1qz4rgp.gif

Later on, the three most well-known rune poem collections were published by Ole Worm [4], Runólfur Jónsson [5] and George Hickes [6]. These are respectively known as the Scandinavian, Icelandic and Anglo-Saxon rune poems. The Scandinavian and Icelandic collections each contain sixteen runes, while the Anglo-Saxon collection contains twenty-nine. It should be noted that since Norway and Iceland both belonged to Denmark at the time, Worm had access to the medieval runes still in use to some degree in Iceland, and at least a large amount of his knowledge came from those.

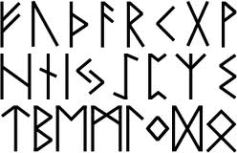

The discovery of the Kylver runestone in Gotland in 1903 revealed another piece of runic history; this stone contained an inscription done in runes from a set which seemed more similar to the Anglo-Saxon runes than to the Scandinavian set, but contained only twenty-four characters. It was deemed to be an older form, and four years later in 1907, Otto von Friesen of Sweden published Runorna i Sverige [7]. The first page of this short pamphlet contained the earlier discovered runes as a set called the Elder Futhark, and it was divided into three, eight-character groups called ættir. The names commonly associated with the runes of the Elder Futhark have since been reconstructed using the surviving Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian names, but direct linguistic evidence for these names has not been found thus far.

The Kylver runestone. Obtained from: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/__CjMqliGoMc/TH_r_LzZ-FI/AAAAAAAAEpc/U2A79h1se7s/s1600/Kylverstenen_2+detail.jpg

Since these advancements in Runology occurred, numerous other works have been published on the subject of runes as well as on the ancient practice of galdur, especially pertaining to its application in runic magic. However, much of this information which has been brought forth is not well supported and is the product of misinformation, uneducated guesswork and new-age fusions of unrelated cultural practices from places as far as Italy and Asia [8].

The root meaning of the word galdur comes from the old Germanic word gala, which was a word for the singing of incantations. Examples of galdur are shown in several Eddic poems including Hávamál [9]and Skírnismál [10]. This verse from Oddrúnargrátr also provides an example of the practice of galdur, though in this particular translation the word is not expressly used [11]:

Þær hykk mæltu

þvígit fleira,

gekk mild fyr kné

meyju at sitja;

ríkt gól Oddrún,

rammt gól Oddrún,

bitra Galdura

at Borgnýju.

Is translated as:

No more spake they,

the mournful ones;

night her, Oddrún

did kneel to help:

stern spells she spake,

strong spells she spake,

for womb-bound woman

witchcraft mighty.

In the Hávamál verses, Oðinn describes eighteen songs that he knows following his description of how he won the knowledge of the runes, which can be used as spells to aid dull an enemy’s blade, break fetters, stop a flying spear, and other feats. In Skírnismál, Skírnir uses galdur to force Gerðr to marry Freyr.

But how are these songs performed? Some authors have attempted to describe techniques of runic galdur, but often their information is short-sighted, or simply false. Some authors such as Thorsson come up short in their presentation of galdur as a simple chanting of the runes’ respective names [12], which seems to be influenced by traditions such as Wicca or ceremonial magic more than anything truly heathen. To discover the secrets of runic galdur, we need to look to the sources, and even to the words of the god of runes himself.

In Hávamál there is contained a short section often known as the Rúnatál. This stanza contains eight lines in a repeating pattern, with one word changed in each to describe a different aspect of runic techniques:

Veistu, hvé rísta skal?

Veistu, hvé ráða skal?

Veistu, hvé fá skal?

Veistu, hvé freista skal?

Veistu, hvé biðja skal?

Veistu, hvé blóta skal?

Veistu, hvé senda skal?

Veistu, hvé sóa skal?

These lines translate to “Do you know how…is done?” with the eight skills of carving/writing, interpreting, coloring, testing, praying, sacrificing, sending and rejecting. Along with the value that these contain in advising the seeker on how to perform runic magic, these verses contain three key elements of Germanic poetry and galdur form: Repetition, rhyming and alliteration. Notice that the first two words of each line are phonetically alliterative and each pair of two successive lines (1-2, 3-4, etc.) contains an interchangeable verb with the same first letter (rista/ ráða, fá/freista, etc.). The structure of the stanza shows an obvious combination of rhyming and repetition in the fact that they begin and end the same, thereby forcing a rhyming quality through the identical end words. Of the three, however, the rhyming quality shows up less in preserved inscriptions and manuscripts, suggesting that it may not have been quite as important.

This alliterative quality of runic verses can also be used as a marker to identify the pre-Christian authenticity of earlier works. Returning to Ole Worm’s Norwegian rune poem, there is a noticeable difference between the first and second line: while the first line in each verse contains alliteration, the only verse in which the second line contains this quality is in that of ós:

Óss er fiestra ferda,

för; en skalpur er sverda.

Other verses are structured such as the poem for Kaun:

Kaun er beggia barna.

Ból giörer near folvarna.

While the rhyme is preserved between the two lines, alliteration is only present in the first, suggesting that these lines may be more authentic than the second lines. The Icelandic poem, however, contains two sets of alliteration per verse. Additionally, there are no Christian influences in the Icelandic poem, while there are several in the Danish poem, further suggesting that the authenticity of the Danish verses may have been compromised, at least in the second lines. The Anglo-Saxon poem also has mentions of ‘the Lord’ throughout some of its verses, but the alliteration is solid, suggesting that the poems have at least some degree of pre-Christian authenticity overall. However, there is one feature to which attention should be paid here. Notice that there is a triple alliteration present in both poems, between first and second lines: “fiestra/ferða/för” and “beggia/barna/ból”. This triple alliteration, in which the beginning of the second line is paired with the alliteration between two words in the first, is present in every poem of the set, suggesting that it follows an alternative, and perhaps older, verse form. It should be noted as well that even with discrepancies or Christiant influences, the Norwegian poems are not to be passed off as “illegitimate” or “worthless”, as much of the other lore has been preserved post-conversion, and likewise these poems still contain important aspects of runic and heathen knowledge. In fact, runic prayers persisted after the conversion had already taken hold, such as this prayer to Oðinn:

“Ek sori þik, Óðinn, með …, mestr fjánda;

j¶¶áta því; seg mér nafn þess manns er stal;

fyr kristni; seg mér nú þína ódáþ.

Eitt níðik, annat(?) níðik; seg mér, Óðinn.

Nú er sorð ok … með ǫllu …

… þú nú ǫþlisk mér nafn þess er stal. A[men.]”

Which roughly translates to:

“I conjure you, Odin, with (paganism), the largest among the devils. Go with it. Tell me the name of the man who stole. For Christianity. Tell me now (your) misdeed. One is taunting me, (the other) mocks me. Tell me, Odin! Now (amounts of devils?) Evoked by all (paganism). You should obtain / Odle me the name of the person who stole. Amen.”

It is easy to conclude that this poem is written from a Christian point of view, beginning with the description of Óðinn as essentially a leader of devils, and ending with the concluding “Amen”. However, this man evokes Óðinn to help him discover a thief, even though he is now viewed as an evil entity.

There is another piece of Norse poetic form which should be addressed; that of galdralag. Stanza 101 of Snorri’s Hátattál is labeled only as Galdralag, with no other description given. This name has been translated as “meter of magic”, leading to the suggestion that the meter indicates a form of verbal magic.[13] This poetic form is believed to be a variant of ljóðaháttur, which translates to “style of songs”. [14]The meter of ljóðaháttur contains several rules over alliteration, number of lines and syllables per line. There are six lines in total; the first pair of lines, called a long line, is an alliterating pair, followed by a single full line with internal alliteration, followed by another alliterating pair, followed by a final line with internal alliteration. The alliterating pairs will contain in each line 3-7 syllables, with two stressed syllables per line. The single alliterating lines are whole unto themselves and will usually be longer, having 5-9 syllables, and there are three stressed syllables; at least two of them forming the internal alliteration. The following verse is an example in English, with the stressed syllables italicized:

Long have I stood,

on Sigtyr’s path.

The ravens were readily fed.

Now years have passed,

and youth is gone.

The sea-steed one last time sets sail.

This meter was very popular up until somewhere between the 14th and 18th centuries, and about a quarter of the poems in the Poetic Edda are written in this meter.

The characteristic variation that separates galdralag from ljóðaháttur is the addition of a seventh line, a single full line with internal alliteration as before, following one of the others. Although not essential, this line will often be a modified repetition of the previous line, adding to its quality as an “incantation meter”.[15] In the Eddic poems which feature ljóðaháttur, the mentions of runes are most often accompanied by the galdralag verse structure. This is not the case every single time, but the solid majority of the runic verses in these poems are done in the this meter. For an example of galdralag structure, see my galdur verse for Þurs further down.

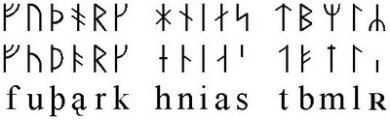

There are also considerations which can be made when writing out runes. Because the runes have names which translated into individual words in their respective languages (e.g “Fé” = “Wealth”), they can be used as ideograms in writing to substitute for the full words. An example of this can be seen in the Stentoften runestone as shown below:

The inscription reads:

<niuha>borumz <niuha>gestumz Haþuwulfz gaf j[ar], Hariwulfz … … haidiz runono, felh eka hedra

niu habrumz, niu hangistumz Haþuwulfz gaf j[ar], Hariwulfz … … haidiz runono, felh eka hedra

ginnurunoz.

Hermalausaz argiu, Weladauþs, sa þat

briutiþ.

Which translates to:

(To the) <niuha>dwellers (and) <niuha>guests Haþuwulfar gave ful year, Hariwulfar … … I, master of the runes(?) conceal here

nine bucks, nine stallions, Haþuwulfar gave fruitful year, Hariwulfar … … I, master of the runes(?) conceal here

runes of power.

Incessantly (plagued by) maleficence, (doomed to) insidious death (is) he who this

breaks.

For those who are wanting an example, the inscription on this stone was done in Proto-Norse, as can be seen by the Elder Futhark runes. Notice, though, that the four last runes in the third line are g,a,f and j, which read as “gaf j(ar)” or “gave (full) year”. Jara, the rune which meant “year” and corresponded to the Proto-Norse /j/, was used here as an ideogram for the word “year” instead of writing out the individual runes to spell the word. Similarly, if one is to write out runes to correspond to a galdr incantation, the text can be shortened using such techniques. Written runic magic was not usually lengthy, though, especially when carved. An example is the Ledberg stone, which contains a galdr verse which reads:

ÞMK – III – SSS – TTT – III – LLL

Reorganized, this reads as:

Þistil, Mistil, Kistil

This translates from Old Norse to “Thistle, Missile, Chest”, the interpretation of which can be made from there. The stone itself is shown below, with the section described on the side of the stone to the right:

This example dates back much further than Galdrabók, and may present an example of an older form of runic magic. While there is no alliteration or actual repetition in this piece, there is noticeable rhyming, which may or may not be done with intent.

When studying runes and the associated galdur practices, it is important to study the rune lore itself. Through examining the grammatical structure of the rune poems and the runic verses in the Hávamál and other source lore, one can gain a solid grasp on the proper technique for performing the ancient practice of runic galdur in the modern world. For a modern example, I will present my personal galdur verses for Þurs and Reiðr. Note that as these verses are in modern Swedish, with the rune names preserved in their Old Norse forms for psychological familiarity as well as to make them more recognizable. The stressed syllables have been italicized in order to identify the vocal emphases as well as the alliteration between and within lines:

Þurs

Þurs gör makt, som forn, är.

Þurs gör makt, som farlig, är.

Jättar kasta ofta kaos.

Þurs gör makt, som forn, är.

Þurs gör makt, som farlig, är.

Nu vill jag har en väldig makt.

Nu förstörar jag mina fruktan.

Reiðr

Ge mig rätta rörelser,

Reiðr, för bekväma färder.

Galdur verses can be as low as two or so lines as seen in the Norwegian rune poems, or they can be longer; there are various sources using different meters and amounts of lines. However, following these general grammatical and structural guidelines will be helpful in forming more authentic galdur verses and techniques. Though Old Norse is not necessarily practical for these applications in the modern world for those who don’t know it otherwise, it is very much possible to adapt these practices in terms of the Younger Futhark to modern Scandinavian languages due to their similarity to the older language, though it is also good to refrain from using loaner words from outside languages such as French, Latin and German which have been incorporated into the modern forms. When dealing with the Elder Futhark, however, it would be most effective to write and perform galdur in their original language of Urnordisk (Proto-Norse), which was a northern variant of the Proto-Germanic language used up until the linguistic transition which brought about Old Norse and the Younger Futhark [16]. Because of its age and the fact that it essentially died out before the Viking Age, it is not nearly as similar to modern Scandinavian languages as is Old Norse. Sadly, not much has been preserved of the Urnordisk language, and the vocabulary is very limited. This creates an obstacle for trying to present authentic galdurs, and until more can be revealed about the ancient tongue, one must work with what options are available. Those who seek, and those who are willing to listen, will find the truths of the runes revealed to them.

Rista stóra stafi!

Rista stinna stafi!

- Enoksen, Lars Magnar. The History of Runic Lore. Scandinavian Heritage Publications. 2011.

- http://www.kb.se/F1700/ABC.htm

- Enoksen, Lars Magnar.

- Worm, Ole. runeR Seu Danica Literatura Antiqvissima, Vulgò Gothica dicta.Hafniæ. 1636.

- Jónsson, Runólfur. Lingvæ Septentrionalis elementa tribus assertionibus adstructa. Hafniæ. 1651.

- Hickes, George. Linguarum Vett. Septentrionalium Thesauri Grammatico-Critici et Archæologici pars prima: seu Institutiones Grammaticæ Anglo-Saxonicæ, & Meso-Gothicæ. Oxoniæ. 1703.

- Friesen, Otto von. Runorna i Sverige. Sommarkurserna i Uppsala. Grundlinjer till föreläsningar.Uppsala. 1907.

- Ralph Blum based his understanding of runes and their techniques largely off of the I Ching of Chinese origin, and many modern runic divination techniques are inaccurately based off of Tarot, which developed in 15th century Italy and had no connections with any sets of runes.

- Hollander, Lee M (tr). The Poetic Edda. University of Texas Press. 1962

- Hollander, Lee M (tr).

- Hollander, Lee M (tr).

- Thorsson, Edred. Futhark: A Handbook of Rune Magic. Weiser Books. 1994.

- Westcoat, Eirik. What Goals had Galdralag? A Look at the Uses of the Meter. 48th International Congress on Medieval Studies. 2013. Accessed 23 Nov. 2013. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/2076311/What_Goals_had_Galdralag_A_Look_at_the_Uses_of_the_Meter.

- Ringler, Dick. III. Formal Features of Jónas Hallgrimsson’s Poetry and the Present Verse Translations. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Accessed 23 Nov. 2013. Available from: http://www.library.wisc.edu/etext/jonas/Prosody/Prosody-I.html.

- Westcoat, Eirik.

- This information was garnered from a private conversation with Lars Enoksen, in which I inquired as to whether or not modern Swedish was appropriate for galdurs applied to the Younger Futhark. Lars asserts that while languages such as modern Swedish can be used with the exclusion of loaner words, the Elder Futhark runes are desirably used in galdur spoken in Urnordisk, otherwise they will not be effective.